What shape does a soul take? For some, they are flourishing gardens. Others have tidy houses — and there are some whose souls are terrifying dungeons. This is called the “soul home,” or nehym. The state of a nehym reflects the person, and everything of that person is embodied in their soul…so what does it mean that Kamai doesn’t have a nehym of her own? And that in every soul, she sees a closed black door her mother warns her never to open? Thankfully, at least, these are secrets to bury, not stigmas to bear, as only a precious few have the goddess-gifted ability to soulwalk, Kamai and her mother included. This means that her mother, Marin, makes an excellent spy. She and her ersatz husband Hallan end up embroiled with an organization called the Twilight Guild. Kamai believed that her mother and Hallan pretended at marriage to mask their true occupations as pleasure artists, but discovers another layer of intrigue—their pleasure artistry serves as the perfect mask for soulwalking, in which the subject needs to be asleep.

Razim, Hallan’s son and two years Kamai’s senior, compounds Kamai’s discomfort with their parents’ espionage by emphasizing the sexual nature of their tasks, as well as the sexual relationship Marin and Hallan share. Kamai isn’t merely uncomfortable because it involves her mother. As she approaches her eighteenth birthday, she’s confident that not only does she have no interest in sex, the thought of it repulses her. Strickland emphasizes that though Kamai occasionally experiences aesthetic attraction to people of any gender, she is uncomfortable with sex and has little interest in romance. It hadn’t presented problems in her youth, but as they age, Razim’s behavior turns increasingly towards attraction. This becomes the least of Kamai’s worries. Secret identities, hidden plots, and court intrigue unfurl when the Twilight Guild turns against Marin and Hallan—and murder them in their own home, in front of Kamai.

The last words her mother speaks beseech Kamai not to trust any members of the Twilight Guild—including Razim. Fleeing the burning ruins of her beloved home, Kamai finds herself caught directly in his arms. He binds her and tells her it was not, after all, the Twilighters who killed their parents, but men acting directly on the order of the king.

The true ruler of the realm in Beyond the Black Door is Ranta, the earth goddess, the daughter of Tain and Heshara, the sun god and moon goddess. The mythology of Tain and Heshara governs the world, and soulwalking is a gift from Heshara. The story goes that Tain and Heshara spent their existence fleeing the Darkness, until they had Ranta. They made a home for their child, and now spend every day circling her to keep the Darkness at bay.

So Ranta rules the earth as queen—in essence. In practice, this means that every king who rises to power must pledge a sacred oath to the earth goddess…and then he may rule as he pleases. Furthermore, he needs to produce heirs, so he marries a human woman who becomes his queen consort. Razim insists that it’s the king who murdered his father and Kamai’s mother, and he swears to murder the king in return.

As Kamai struggles to untangle the increasingly complex web of court intrigue, political assassins, and long-held secrets that led to her mother’s death, she also must contend with a dark and increasingly powerful creature within the recesses of her own mind. Enticed by rose petals and her own curiosity, she does what her mother always told her never to do: she opens the black door. The being behind it calls himself Vehyn, and he’s not human. He refuses to tell her what he is or why he’s there, and he begins to demonstrate an enormous power over her, whether she’s soulwalking or awake—including the ability to see the world through her eyes, and control her movements. Kamai is horrified and frightened, but also finds herself inexplicably drawn to his power, especially because he never masks his attraction to her. He too feels no desire for sex, but she comes to question her own limited romantic attraction in the face of her developing feelings for Vehyn.

The relationship between Kamai and Vehyn drives the plot as much as the court intrigue, and it’s a fraught one. He is unquestionably toxic: possessive and manipulative, vicious and deliberately frightening, and he wields an eerie amount of power over Kamai’s body and fate. Fans of the romance at the center of Labyrinth or Phantom of the Opera may enjoy the dynamic that emerges between them. A sort of twisted love triangle emerges (no spoilers!) with Razim, who holds attraction for her even though, as she emphasizes to him, despite sharing no parentage, they were raised as siblings. Ultimately, the romance allows Kamai to reclaim her own body and desire, and refocus on the positive presences in her life.

Beyond the Black Door is substantially queernormative, with multiple characters expressing gay or queer desire, and Kamai’s sex-repulsed asexuality is explored on the page. I don’t share this identity, though the author does, so I cannot speak authoritatively to the depiction. For this particular narrative, that means that Kamai does manifest internalized acephobia, which comes up as a significant plot point when she’s asked to perform pleasure artistry for the sake of soulwalking. It’s also a point of contention for both Vehyn and Razim. Her acephobia is also eventually checked on the page, but asexual readers may want to be aware that it is pervasive, and before she confronts it—and she does!—she conflates it with her perceived lack of a soul home.

[Note: The author’s content and trigger warnings for this novel can be found here.]

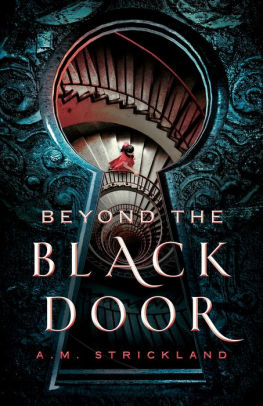

Buy the Book

Beyond the Black Door

One of the loveliest moments of the narrative involves her literally exploring the spectrums of gender, sexuality, romantic attraction, and sexual attraction in a safe space with welcoming queer allies using a waning and waxing moon chart. It is here that she discovers a secret about the head of her father’s guard, one of her dearest companions within that household. Kihan is also asexual, and he’s “soul-crossed,” a trans man. Strickland, who identifies as genderqueer, chooses to use Kihan’s deadname and birth pronouns throughout most of the novel. Their reasoning is that Kihan, like many trans folks, isn’t ready to out himself for personal and professional reasons, and becomes more comfortable with himself through time. Trans readers may want to be aware of this choice.

The asexual and specific transgender experiences explored in this novel are not mine, but they are valid. As Strickland has mentioned themself, some readers may find the renderings of these experiences uncomfortable, and some may find them helpful and vindicating. All the queer and trans narratives are ultimately well-received within the context of the novel.

The plot is complex and the pacing ambitious. Beyond the Black Door is at once a twisty, atmospheric dark fantasy built on rich mythology as well as an emotional story of coming into one’s own identity and power.

Beyond the Black Door is available from Imprint.

Read an excerpt here.

Maya Gittelman is a queer Pilipinx-Jewish diaspora writer and poet. Their cultural criticism has been published on The Body is Not An Apology and The Dot and Line. Formerly the events and special projects manager at a Manhattan branch of Barnes & Noble, she now works in independent publishing, and is currently at work on a novel.